High and Dry

In northern California, wildlife and marijuana growers battle for water.

By Erin McHenry

Scott Bauer trekked through the California hills, following a winding path of dirt. Only a few years ago, it flowed with rushing water, rippling with salmon and trout. But the fish are mostly gone now, only a few remain in small pools left behind by the dried-up stream. “The Coho [salmon] that were still alive in those pools, they were so skinny,” said Bauer, a salmon researcher for the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. When the river ran dry, the fish were trapped with no food and no exit strategy. Many starved.

A bird’s-eye view of the hills reveals the stream isn’t the only change in Humboldt, Trinity and Mendocino counties. The woodlands have been replaced by marijuana grow sites. In Humboldt County, that’s roughly one grow site every square mile.

According to the Oregon Department of Justice, an average marijuana grow site — approximately 1,000 plants — uses about 5,000 gallons of water a day, more than 1,200 showers. In northern California, most of that water is diverted from local streams and rivers, the salmon’s home.

So when the marijuana industry boomed in 2010, thanks to a California Supreme Court ruling (more on that later), local waterways suffered. And it couldn’t have occurred at a worse time. California is experiencing extreme drought conditions according to the National Drought Monitor. It could potentially be the worst in 500 years, Mother Jones reported.

The creeks are already low — hardly flowing along, Bauer said. Add on water diversions of 10 or more gallons per minute, and there’s little left for the salmon.

“We have hundreds of grows in each of those watersheds, which is thousands of plants, and over the course of the summer you start to reach millions of gallons of water,” Bauer said.

Each gallon of water used for the plants encroaches on the salmon’s home. Marijuana is quickly usurping the watershed and the land, and the negligence of its growers is quite literally leaving the wild salmon out to dry.

The New Gold Rush

Northern California’s marijuana culture has existed for years. Medical marijuana had been legal since 1996 when California passed Proposition 215, but it wasn’t until 2010 that the industry of growing really exploded.

In 2010, the California Supreme Court ruled in People v. Kelly that no limits could be placed on the amount of marijuana a person could grow. Up until that time, one person could only have eight ounces of dried marijuana, six mature plants or 12 immature plants.

Suddenly, growers had the right to legally produce as much marijuana as they liked — only for personal consumption, of course. Patients and primary caregivers were protected for personal use or cultivation, but not for distribution or commercial sale.

These lines are easily blurred, however; and soon, marijuana users and entrepreneurs saw promise in California. It wasn’t long until people from around the world flocked to the West Coast, not unlike the great migration of gold-hungry Americans in the mid-1800s. But this time, it wasn’t gold they were after.

It was called the “green rush.”

“It was just like rapid industrialization in our area,” Bauer said. The amount of land under marijuana cultivation doubled in Mendocino and Humboldt counties from 2009 to 2012. There are 4,100 marijuana grow sites in Humboldt County alone. Add in Mendocino and Trinity counties, which have nearly as much weed as Humboldt, and it’s understandable why this area quickly developed a new nickname: The Emerald Triangle.

Now only 4,000-5,000 Coho salmon come back to California rivers and streams.

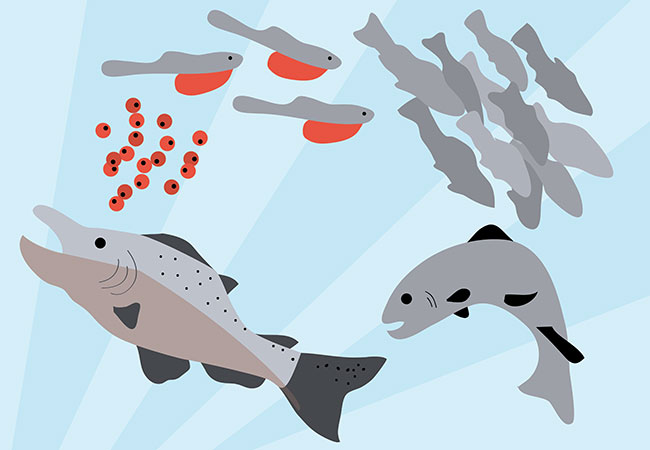

The Plight of the Salmon

With thousands of grow sites in a concentrated area and with each of them using approximately 5,000 gallons of water every day, all that water has to come from somewhere. In Humboldt County, just one season of a dried-up stream could make a lasting impact on the wild Coho and Chinook salmon populations. After a number of dry years, Bauer said, the salmon coming there to spawn will have diminished. The only hope for those streams would be that salmon arrive accidentally, as a result of getting lost on the way back to their own spawning grounds.

“If the whole population of fish in a larger watershed like the Eel River is already depressed and at low numbers, the possibility of straying is so remote, you may be looking at decades before those streams get repopulated,” Bauer said.

Each time a stream dries up, a class of fish dies, and the population (deemed endangered by the National Wildlife Federation diminishes a little more.

Historically, there would be 200,000 to 400,000 Coho salmon returning to California each season, said Peter Moyle, professor of fish biology at the University of California-Davis. Now he estimates there’s only 4,000-5,000 coming back in the most populated California rivers and streams. And Coho and Chinook salmon, as well as Steelhead trout, were already in tough waters back in the ‘40s and ‘50s when logging companies destroyed their habitats. Diverting that water destroys the few strides that have been made towards salmon recovery.

“Right now, you’ve got these tiny remnant populations that are just hanging on there,” Moyle said. “It used to be that marijuana was surreptitious and only happening on public lands. But now it’s out in the open. And they’re literally drying up some of these small tributaries.”

Chinook (also known as King) is already the least common salmon species, but the fish themselves are the biggest in size. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the average Chinook reaches three feet in length by adulthood, and weighs about 30 pounds. Their meat is especially tender, red and typically most expensive of all salmon breeds. Coho tend to be smaller and live in smaller streams and tributaries. Both live in cold-water habitats

“People love eating salmon,” Bauer said. “If we lose Chinook, where are we going to get that food source?”

However, the issue transcends a crispy, fresh filet on the grill. Chinook and Coho salmon provide vital fertilizing nutrients to the surrounding wildlife. After death, their decomposing carcasses provide food for small invertebrates and bring phosphorus, nitrogen and elements of the Pacific Ocean back to the freshwater.

“It’s found in everything,” Bauer said. “It reverberates through the food chain. Those critters, not just the salmon, but everything else that feeds on it that’s supported by it, would be diminished.”

Take grizzly bears, for example. Salmon is one of their main food sources, so a shrinking fish population impacts bear population, body size and the number of cubs a mother will have. As wild salmon has become scarcer, the bears have shown physical reactions to the waning food supply.

“We found that bears that are eating less salmon have higher levels of this stress hormone cortisol,” said Heather Bryan, researcher for Raincoast and the University of Victoria. “There could be a couple of reasons for that. One would be that the bears are nutritionally stressed because they’re not getting enough salmon to eat, and another possibility is that it causes social stress because it creates more competition. Either way, elevated stress hormones indicate that bears might respond to salmon declines with unknown but potentially negative effects on health and reproduction.”

Without salmon, the grizzlies suffer, and so do the coastal forests. Bears bring salmon carcasses to the forests, which act as fertilizing agents to inland wildlife. The nutrients are found in the soils, grasses, even the towering redwoods of the Sequoia National Forest.

“We consider [bears] to be vectors of nutrients from the marine world to the terrestrial world,” Bryan said.

Pot Pollution

Growers are abusing the water supply, but California doesn’t have much water to spare in the first place.

According to the Western Regional Climate Center, California averaged seven inches of rainfall for the entire 2013 season — its driest year since 1898. And 2014 doesn’t look much wetter. In Humboldt County, rain totals are half the usual amount by this time of year.

Water loss isn’t an entirely new phenomenon in California. NOAA estimates California has lost 91 percent of its original wetlands. The California water supply is already low, so the additional misuse from growers leaves northern California parched, to say the least.

But the streams, rivers and tributaries that have escaped complete dehydration aren’t safe, either. Fertilizers used on the marijuana plants often run off into the water, causing over-nitrification of streams. The fertilizers bring too many nutrients to the water, squandering its oxygen supply, and creating a desirable habitat for blue-green algae blooms.

“All of these streams run down to bigger rivers that are used for drinking water,” Bauer said.

These blooms have been found to cause rashes, upset stomach, or eye irritation, according to the California Department of Public Health. In large quantities, the blue-green algae can cause tumors, liver toxicity, even death.

“If your dog drinks the water, it’s dead in 30 minutes,” Bauer said.

And just constructing a grow site could be enough to dictate the longevity of salmon’s life. When plowing, digging and clearing out land in the mountains, dirt and sediment spills over into the water. It clogs up streams and can tamper with salmon spawning abilities. After that, many growers use diesel or propane tanks to power indoor sites, and those tanks sometimes leak into the water system – and leak into salmon gills from there.

Altogether, each simple decision a grower makes, combined with the pre-existing environmental conditions, spells out a recipe for disaster for Coho and Chinook salmon. As the circle of life suggests, each part is connected, and when one of them is in jeopardy, everything is susceptible somewhere down the line.

Moyle worries especially about the Coho salmon that live more commonly in smaller streams and are less resilient to environmental stressors, like water temperature.

“It’s facing extinction in this state,” he said.

Field researchers inspect what was once a stream and home to many salmon, dried up in 2013 from water misuse.

Instilling A Sense of Responsibility

Marijuana itself can’t take all the blame. The real problem is negligence, Bauer said. There are laws and regulations in place to conserve and protect the environment from these problems, but the responsibility falls on the growers.

“We need people to care,” Bauer said. “Those who are growing need to work with us. To reduce water. To store water. To develop tanks and ponds to store water from winter rains so they don’t have to use summer water from the creek. … We just need them to participate.”

And participation can be difficult to motivate.

“I don’t think they realize it’s a death by a thousand cuts,” Bauer said. “One grower might take just 10 percent of a stream, but further down someone else takes 10 percent, another takes 20 percent, and soon enough there’s nothing left to take.”

It’s a complex issue, with no definitive solution in sight.

The National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML) proposes complete marijuana legalization (recreational included) as the best option.

Regulation isn’t so simple, however. It’s a quasi-legal situation, Moyle said. Most people are legally allowed to grow marijuana for medicinal purposes, but many skirt around the rules and produce commercially, anyways.

“Its becoming large scale farming, essentially,” he said.

Like any other form of agriculture, there are regulations dictating water, fertilizer and pesticide usage. But rules can be broken.

Even with laws in place, the trend isn’t likely to change until growers make an active effort to conserve the surrounding landscape on their own accord.

“We have to put the pressure on them to grow the products ethically because we the consumers want it that way,” said NORML Executive Director Allen St. Pierre. “Not the government, not syndicated crime, not pop culture; it’s the consumers. It’s the consumers that say ‘You know what, I’m going to have things done differently.’”

Nonetheless, when growers produce for a profit, they look for efficiency.

“If the product is made, particularly in a large industrial capacity, those who want to grow it efficiently will use fertilizers and they will use pesticides in greater amounts,” St. Pierre said. “How can that be done better ethically with an environmental ethos in place?”

Motivating consumers to demand a more environmentally conscious product may get some growers’ attention, but ultimately, change will start with the growers.

“People come to grow here because they think there’s abundance of water and cheap land,” Bauer said. “Well, the reality of it is there may be some cheap land, but the water isn’t as abundant as people think. A couple of users in the watershed who are growing a lot of plants can use up all the water pretty easily.”

And without any rain to restore the supply, the resources won’t last forever.

Bauer hasn’t been back to that dried-up stream. He wonders how it looks now. Parched like the rest of the state? Crippled, and limping along, reduced to isolated pools of groundwater? He doesn’t know, but he’s willing to bet: There won’t be any salmon there.

“It’s the web of life,” Bauer said. “You pull one part of it and the whole thing comes unraveled.”

He can only hope someday, somehow we’ll be able to put it back together again.

Photo courtesy of Scott Bauer; Illustrations by Olivia Curti

Medical Marijuana Saves the Lives of Children

Kids with severe epilepsy are seeing dramatic results from a strain of marijuana called “Charlotte’s Web.”

It was bedtime for Zaki. His mother, Heather Jackson, went through the routine of pulling together a makeshift bed next to her own and tucking her 10-year-old son into the blankets. He couldn’t sleep in his parents’ bed tonight — Dad had to work in the morning.

Tell us what you think