The Tale of Two Cities

Milwaukee, once a safe haven on the Underground Railroad is now the most segregated city in the country.

By Bailey Berg

Maria Ryan-Young expected the cold. She expected the cheese. And, she expected the “Midwest Nice.” But, when she moved to Milwaukee from New Zealand, she never expected she’d be living in the most segregated city in America.

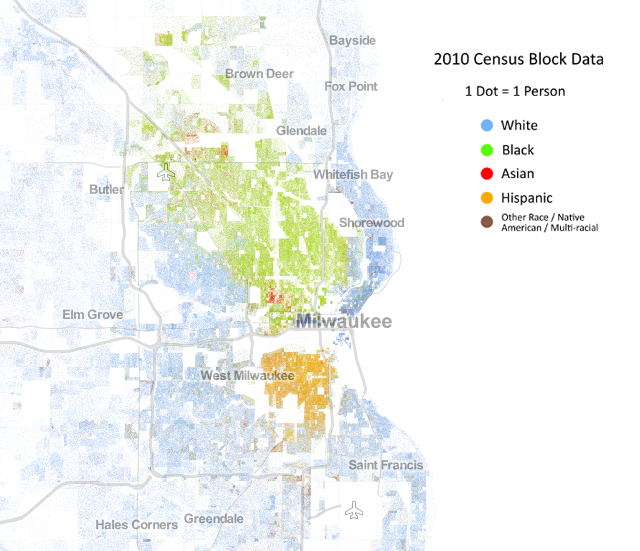

“It’s been interesting as an outsider looking in and seeing the segregation,” Ryan-Young said. “Physically there is a very strong dividing line between the racial groups in the city. There are very defined ‘areas’ of the city. You literally cross the street and it goes from being completely white to completely black.”

While today’s black population isn’t organizing bus boycotts, lunch counter sit-ins or drinking from separate water fountains, they, and many other minority groups, are still feeling the effects of continued segregation.

Travonte Buckley, a 20-year-old student at Wisconsin Lutheran College, grew up in a predominantly black neighborhood in Milwaukee. He described Milwaukee as a tale of two radically different cities in one, separated by invisible boundaries with visible contrast.

“I’ll go to a white friend’s house on the other side of Milwaukee and everything about their neighborhood will be different from my neighborhood,” Buckley said. “That’s just how things are. I’m sure it’s like that for a reason. I just don’t know why.”

Modern-Day Segregation

It’s been almost 60 years since the Supreme Court put ended “separate but equal” facilities with Brown v. Board of Education. It’s been another 40 years since President Lyndon B. Johnson passed the federal Fair Housing Act. But studies show our history of discrimination is far from behind us.

Using 2010 Census data, professors John Logan and Brian Stults at Brown University and Florida State University, respectively, ranked overall segregation in the nation’s major metropolitan areas. Milwaukee — a city that was once the destination for escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad — was revealed to be the most segregated city in the country.

Image Copyright, 2013, Weldon Cooper Center for Public Service, Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia (Dustin A. Cable, creator)

Logan and Stults’ work measured “dissimilarity,” referring to the percentage of each racial group would have to move to a different neighborhood to purge the area of segregation. Milwaukee scored 80 percent for white-black dissimilarity and 57 percent for white-Hispanic.

The second most segregated city is Detroit. In fact, of the top 10, four are in the Midwest, four are in the Northeast and two are in the South. It’s not until number eight on the list that a southern city makes its first appearance with Birmingham, Alabama.

Logan and Stults also found while blacks are only 13 percent of the total population, they typically live in a neighborhood that is 45 percent black.

Turns out, we’ve spent the last 50 years integrating our schools but didn’t look at integrating our neighborhoods.

Milwaukee’s History of Segregation

Buckley wasn’t surprised by Milwaukee’s dissimilarity, nor was ReDonna Rodgers, who moved to Milwaukee in 1981.

“Oh, we hear that all the time about Milwaukee being segregated,” Rodgers said.

Marc Levine, a professor of urban history and development and cultural diversity at University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee, said Milwaukee has been near the top of the list in various studies for more than 30 years. But the history of segregation extends long before that.

Until the end of World War II, the black population in Milwaukee was relatively low. However, between 1945 and 1970, the city’s black population grew by more than 700 percent from 2 percent of the population to 14.7 percent.

“When that first large group of African-Americans migrated to the Milwaukee area 50 or 60 years ago, the housing market was particularly restricted,” Levine said. “There were all sorts of zoning ordinances that made it hard to get affordable housing for them. As a consequence, that explains why Milwaukee tends to be even more segregated than very segregated cities like Chicago, Cleveland or Philadelphia.”

In 1968, the Federal Open Housing Act was passed, which made segregated housing illegal. At least on paper. Though no longer legally required to live separately, the more than 2 million people in the Milwaukee metro have largely stayed put. In 1965, 90 percent of Milwaukee-area blacks lived in the inner city. That number still holds true today.

“We have the lowest level of black suburbanization of any urban area in the country,” Levine said. “Less than 10 percent of blacks live in suburban areas.”

Detroit, as No. 2, doesn’t even come close. Levine said that roughly 20 percent of blacks in Detroit live in suburbs.

Rodgers thinks that’s partly due to personal preference. “Some people like to live where their people live,” Rodgers said. “People live where they feel comfortable. Some people don’t like mixed-race environments.”

Levine agrees to an extent. “There may simply be a sense that the suburbs aren’t particularly welcoming places,” he said. “There have certainly been rather heated demonstrations when affordable housing has been suggested, and it’s usually seen as racially coded. There’s an element of hostility and a legacy of discrimination.”

Another problem facing minorities in Milwaukee is an inability to get to higher-paying jobs in the suburbs because of the lack of public transit from the inner city. Levine said Milwaukee is one of the few major metro areas in the United States that doesn’t have a rail system — either in operation or in planning. Gov. Scott Walker even took the lead in a campaign against public transit to connect the suburbs to the city during his time as county executive. He thought the funds would be better spent on highways.

“Linking to the central city is a politically sensitive topic here,” Levine said. “Legislators think it’ll bring undesirable folks into their community, and the issue of crime is often raised in conjunction with it.”

However, Rodgers said the greatest problem with segregation isn’t the inability to get jobs or live in better neighborhoods, rather a general misunderstanding created about each other.

“If someone lives in an area with people that are only their color and associate only with them, is that bad? No, that’s not bad,” Rodgers said. “But how can people understand each other when they are never around people who don’t look like them? That’s when segregation really becomes a problem. When you are never around other people you don’t get to know the true them.”

Levine thinks that could result in a change of attitude that Milwaukee desperately needs. “A change in attitude and policy would better knit together the region,” Levine said. “I think if those things happen we can have a softening in the level of segregation here. But we have a long, long way to go from here.”

Photo courtesy of coopercenter.org & Jeramey Jannene

A Woman’s Place in the Church

For Mary Kay Kusner, priesthood wasn’t an option — until she had an out-of-body experience.

Full Circle is a small Catholic church in Coralville, just outside Iowa City. It only has a few rows of chairs; about 20 people fill them. Everyone knows each other. They greet one another with warmth then settle in their seats, which is when Mary Kay Kusner walks to the front of the room. She’s in her white robe. She stands at the altar, stretches out her arms, then calls the Mass to order…

Tell us what you think